CONNIE CARBERG BLAZED TRAIL AS FEMALE NFL SCOUT

“I just said OK.”

That’s what Connie Carberg — the first female scout in the NFL — said when she was told new Jets owner Leon Hess didn’t want a woman traveling on behalf of the team anymore. It was 1978, an age when game tape was reel-to-reel. When player reports were typed on paper and carefully tucked into file cabinets. No cellphones, no voicemail.

It was an era when a woman couldn’t easily appeal a demotion based on gender rather than job performance, no matter how much it stung. No matter how badly she wanted it.

“I just didn’t think that way,” Carberg said.

Carberg continued to work in the Jets front office for a time but missed traveling as a scout. So when her husband had a job opportunity in Florida, they decided to take it. Carberg moved on, raising a family in Coconut Creek. But she has never been far from football or from the team she loves. This summer, like almost every other, she will head to Jets training camp with her critical eye and the heart of a fan.

Connie Carberg fell into the role of scout for the Jets after proving her muster evaluating local talent.

Carberg had grown up around the Jets, with a father and uncle who were team doctors. Her uncle was James Nicholas, the Jets orthopedist. Her dad, Calvin Nicholas, the team’s internist, hosted the likes of quarterback Joe Namath and coach and general manager Weeb Ewbank in their Long Island home. As a girl, she would hold her own mock drafts from her home in Babylon. She lived about 20 minutes from the Jets practice facility at Hofstra.

Carberg played sports and spoke football; that’s just how it was in her house.

“I thought every girl did this kind of thing,” Carberg said.

In the era just before Title IX, when women started regularly getting scholarships, Carberg played basketball for two years at Wheaton before transferring to Ohio State. Legendary football coach Woody Hayes took a liking to her and let her attend Buckeyes practices. When she graduated from Ohio State in 1974, with a degree in home economics, she headed back to New York. Jets coach Charley Winner asked if she would be the team secretary.

It was a dream job. The Jets had won a Super Bowl III just a few years prior with Namath at quarterback.

Carberg quickly became a favorite with co-workers, players and fans. She baked pies for the front office staff and coaches and would get players to come to the phone when fans would call to speak to their favorites. She walked into the locker room and yelled “Girl back!” so many times the team jokingly made it her nickname.

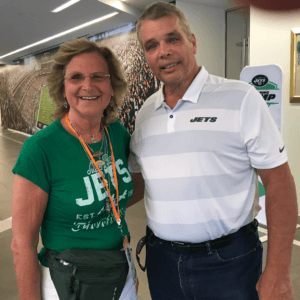

From left, Connie Carberg’s father Dr. Cal Nicholas, New York Jets general manger Mike Tannenbaum and Carberg at the Jets celebration of the 40th anniversary of Super Bowl III.

As the team expanded, her knowledge of the game led Carberg to the scouting office.

Carberg would take home game tape, watch it and write reports. Before long, she was checking out local players the Jets were eyeing. She was doing such a good job that when the Jets needed to add a traveling scout, Ewbank made a radical suggestion to then-coach Walt Michaels.

“She’d go nearby and the reports she wrote were very good,” Michaels said. “Weeb said, ‘Why are we fooling around when we have a good one right here?'”

Michaels didn’t need convincing. To him, it just made sense. Carberg already had information on all the key recruits. Most of it was in her head, and when it wasn’t she had all the right phone numbers.

So what if the NFL didn’t have a lot of women working in a football capacity at the time?

“It was very unusual, but you had to know Weeb Ewbank,” said Michaels, now 80. “He said, ‘She knows more than a lot of guys we got hanging around here.'”

A few things stand out for Carberg out during her six-year tenure with the team.

She got to make decisions on who the Jets would draft. In 1975, she made the Jets pick in the 17th round — a tight end named Mike Bartoszek from Ohio State. She was just happy he wasn’t the first one cut that summer.

“She always thought her pick was going to be All-Pro or player of the year,” Michaels said with a laugh.

Then there was the role she played in getting Mark Gastineau. She made contact with the defensive end and brought him to the team’s attention before the 1979 draft.

Wide receiver Wes Walker said Carberg was the first person from the Jets he ever spoke to, right after he was drafted in 1977. Walker was legally blind in one eye, which scared some teams. But the Jets took a chance on him and it paid off handsomely. Walker was a Pro Bowl receiver in 1978 and ’82 and was named the team MVP in 1978. And, over the years, Carberg and Walker, now a physical education teacher in Long Island, have remained friends.

Walker also remembered how he could never get Carberg to go on a date with him — despite his best efforts.

“I never could make any headway with her,” Walker said.

Carberg deflects questions about the challenges of being a woman about as deftly as she must have deflected player compliments. She said she wasn’t bothered by it or resentful, because she was the rare woman with the team — one with enough audacity to want a part in football operations.

“I never felt when I talked to guys that they thought, ‘Who does she think she is?'” Carberg said.

Carberg knew football, so much so that when she and her husband moved to Florida, she could have pursued a job with the Dolphins.

“I could never bring myself to work for the Dolphins because my loyalty [to the Jets] was so strong,” Carberg said.

And that’s the same loyalty that keeps bringing her back to Jets’ camp year after year, whether it was in Long Island or Cortland, N.Y. Her son and stepdaughter grown, Carberg will return to evaluate the skills she sees on the field again this summer. She will talk to old friends about team dynamics, and she will hope this is the year the Jets get a bookend for the Lombardi Trophy.